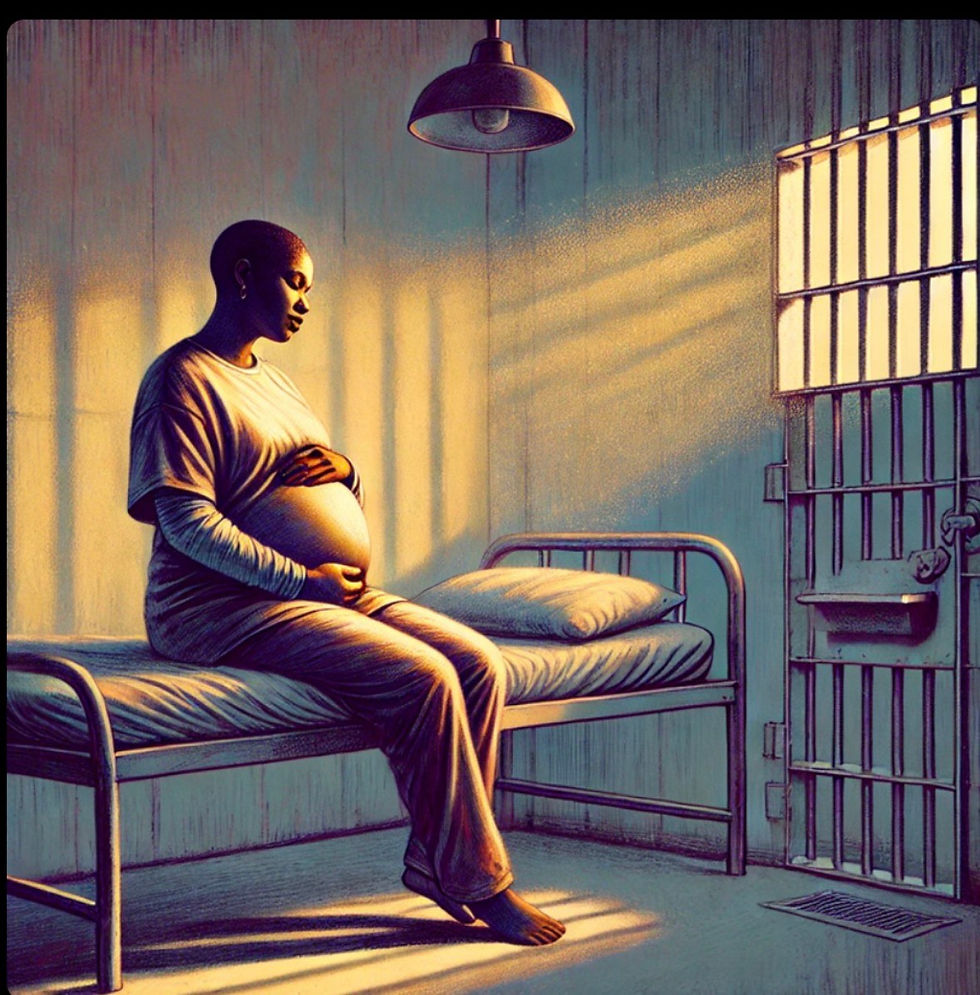

Pregnant Behind Bars: Motherhood Inside the U.S. Carceral System

- Clover Perez

- Dec 29, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: 6 days ago

In the United States, pregnancy does not shield women from incarceration, nor does incarceration meaningfully adjust itself to the realities of pregnancy. Each year, women enter jails and prisons, already pregnant or discover they are pregnant after being taken into custody, and their pregnancies proceed inside systems structured around security, compliance, and cost containment rather than maternal health. Despite the scale of the issue, pregnancy in correctional settings remains largely absent from public debate, addressed sporadically through litigation, policy memos, or advocacy reports, but rarely examined as a systemic condition with profound implications for public health and human rights.

Pregnant women in custody encounter a correctional environment that is not designed to support consistent medical care. In jails, where people are detained pretrial or serving short sentences, women may be transferred, released, or moved to court with little notice, disrupting prenatal appointments and limiting the ability of medical staff to provide continuity of care. In prisons, where incarceration is longer-term, access to obstetric care often depends on external providers, transportation logistics, and facility resources, resulting in delays and limited patient choice. What would be considered basic prenatal care in the community is frequently subject to administrative approval in custody.

Nutrition presents a related challenge. Standard correctional meals are not calibrated to meet the dietary requirements of pregnancy, and access to supplemental food, prenatal vitamins, or medically indicated diets varies widely across facilities. Pregnant women often rely on commissary purchases or advocacy by outside family members to meet basic nutritional needs, creating disparities that mirror broader inequities within the correctional system.

The psychological impact of incarceration during pregnancy is significant. Many women in custody have prior histories of trauma, including intimate partner violence, sexual abuse, housing instability, and untreated mental health conditions. Incarceration introduces additional stressors, including isolation, lack of privacy, restricted movement, and uncertainty about legal outcomes. During pregnancy, these stressors can exacerbate anxiety and depression, yet mental health support is frequently limited, and emotional distress is sometimes treated as behavioral misconduct rather than a medical concern.

Labor and delivery represent another point of tension between medical necessity and correctional control. Pregnant women in custody are typically transported to hospitals under guard, and their movement and interactions may be subject to security protocols that conflict with patient-centered care. Although restrictions on the use of restraints during labor and delivery have expanded in recent years, enforcement varies, and the presence of correctional officers during childbirth remains common. The medical event of giving birth is thus shaped by surveillance and institutional authority rather than clinical autonomy.

Following delivery, incarcerated women often face rapid separation from their newborns. Unlike women in the community, who typically recover with family support and ongoing medical supervision, incarcerated mothers may return to custody within days, with limited opportunity for bonding or breastfeeding. Postpartum care is inconsistent, and mental health screening and treatment during this period are frequently inadequate. The effects of separation are not limited to the mother; early disruptions in maternal-infant bonding have implications for child development and family stability.

One of the reasons pregnancies behind bars remain underexamined is the lack of comprehensive data. For decades, correctional systems did not systematically track pregnancy outcomes, making it difficult to assess risks, identify patterns, or evaluate the impact of policy changes. While data collection has improved in some jurisdictions, gaps remain, particularly in local jails, where high turnover and fragmented record-keeping limit transparency. Without consistent reporting, accountability is uneven, and harmful practices are more difficult to challenge.

Efforts to address pregnancy in custody have primarily focused on policy reform rather than

structural change. Anti-shackling laws, improved medical guidelines, and expanded data

collection represent essential steps, but they do not resolve the underlying tension between incarceration and maternal health. Alternatives to incarceration for pregnant women, particularly for nonviolent offenses, have been proposed as a means of reducing harm while maintaining public safety. Yet, such approaches remain unevenly implemented and politically contested.

The treatment of pregnant women in custody raises fundamental questions about the purpose of incarceration and the responsibilities of the state. Pregnancy introduces medical, ethical, and social considerations that extend beyond punishment and into the realm of public health.

When correctional systems fail to support pregnant women adequately, the consequences extend beyond individual cases, affecting children, families, and communities. Pregnancy behind bars is not an anomaly but a recurring feature of the U.S. criminal legal system. Understanding it as such requires moving beyond isolated incidents and toward a sustained examination of how incarceration intersects with reproductive health. Any serious conversation about justice reform, maternal health, or family stability must confront the realities of pregnancy in custody—not as a marginal issue, but as a measure of institutional accountability.

Written by Dr. Clover A. Perez

Comments